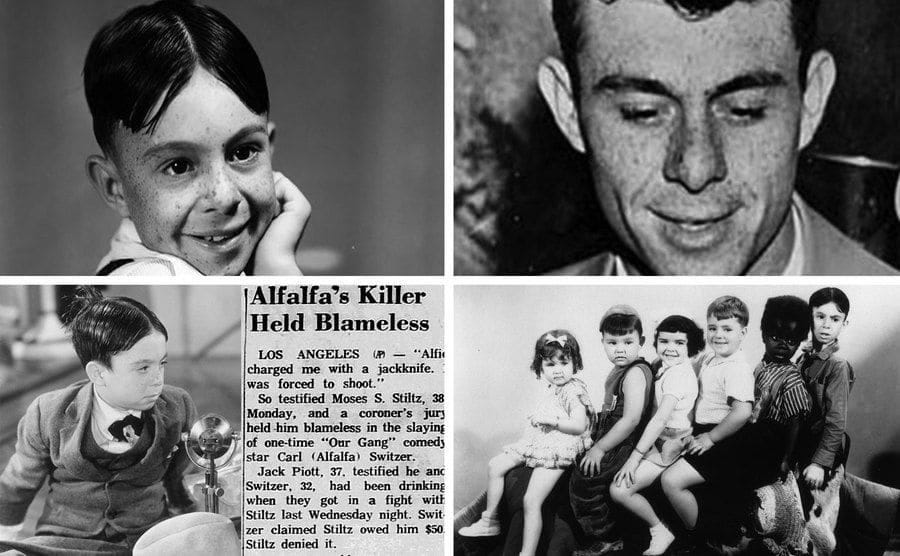

Bobby Driscoll (1937-1968) was hardly Hollywood’s first cautionary tale on the perils of childhood fame. Hal Roach Studios’ “Our Gang” franchise had already set the template for the self-destructive child star, with many of the underage ensemble cast members exhibiting public meltdowns after aging out of marketability. When the “Our Gang” films were repackaged for television syndication as “The Little Rascals,” tabloids were quick to play up the contrast between the wholesome kid faces on screen with the dismal and often scandalous adult lives of the actors behind them.

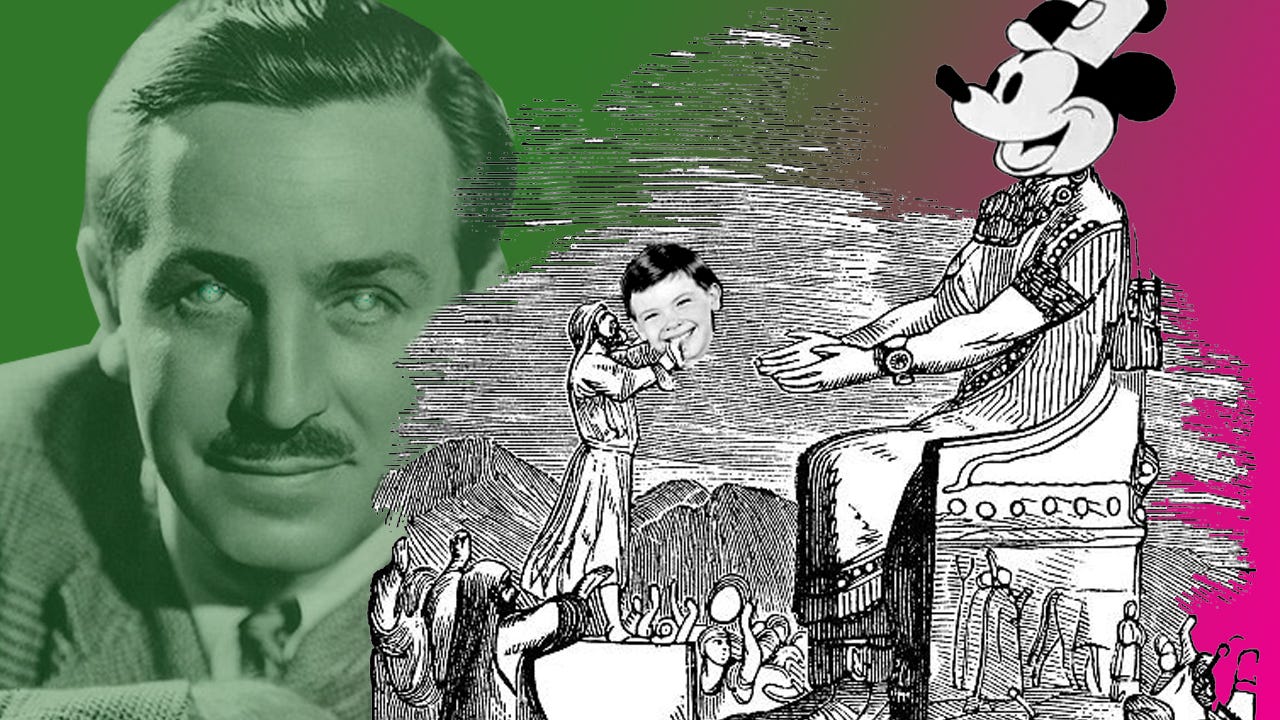

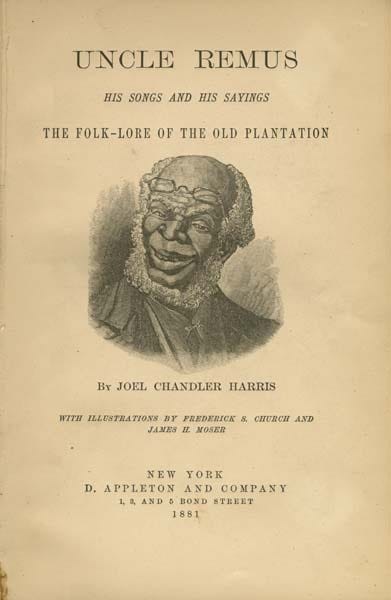

Before building a corporate machine to delegate the task to, Walt Disney took a hands-on approach to ruining the lives of children to benefit his shareholders. Disney had already broken ground with his wildly popular series of short cartoons, Mickey Mouse & Friends. His first feature-length animated film, Snow White and the Sever Dwarfs (1937) was a massive critical and commercial triumph. The Disney studio had been merging live-action with animation for several years by the end of World War II when work began on an adaptation of a collection of folk stories which were originally published by Joel Chandler Harris in 1881.

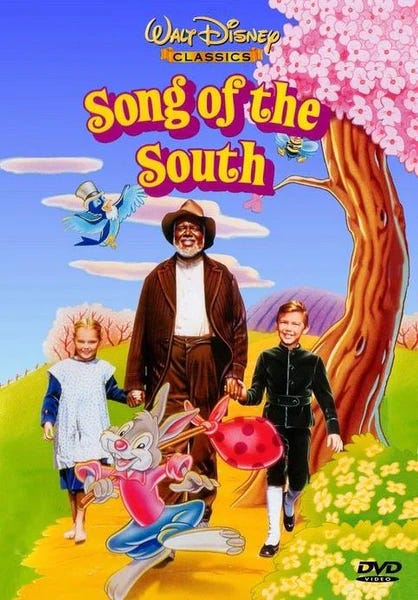

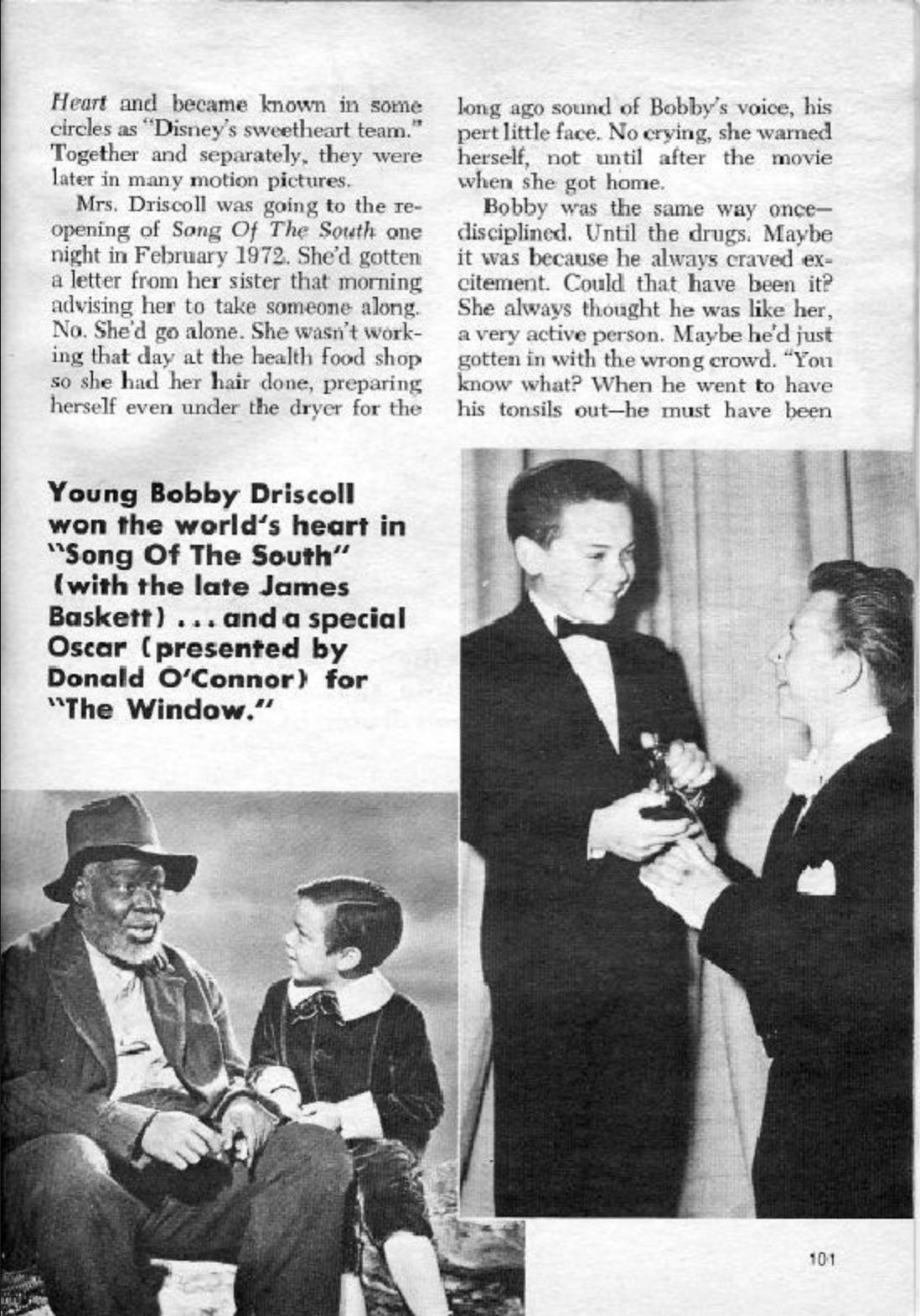

In Song of the South (1946), seven year old Johnny visits his grandmother’s plantation during post-Civil War Reconstruction-era. There he meets Uncle Remus, a jolly black man that lives on the grounds but in separate quarters. Remus regales Johnny with the exploits of Br’er Rabbit, Br’er Fox and Br’er Bear, offering segues into the film’s three animated segments. Song of the South won an Academy Award in 1948 for Best Original Song with “Zip-A-Dee-Do-Dah,” and actor James Haskett was given an Honorary Award for his portrayal of Uncle Remus. The water ride based on the film, Splash Mountain, debuted at Disneyland in 1989. In the wake of the Civil Rights era, a growing distaste for the film’s perceived framing of Uncle Remus as an emancipated slave willingly and gleefully remaining in servitude assured Song of the South would, as of 2023, never see an official home video release, never be broadcast on The Disney Channel and never be made available for streaming on Disney+.

But in 1946, Walt Disney had a lot more latitude to indulge his penchant for intolerance among other vices. Walt recognized incorporating live-action footage into hand-drawn cel animation required hypersaturated colors and faces that photographed well in Technicolor. Early on in the casting process, a nine year old auditioning for the role of Johnny immediately stood out of the pack. Walt knew he was seeing something…special…

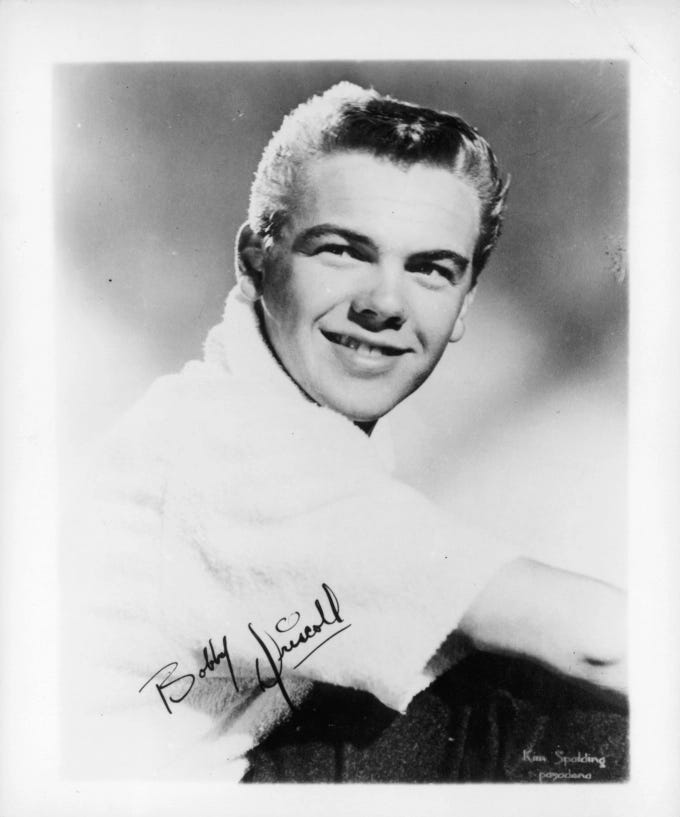

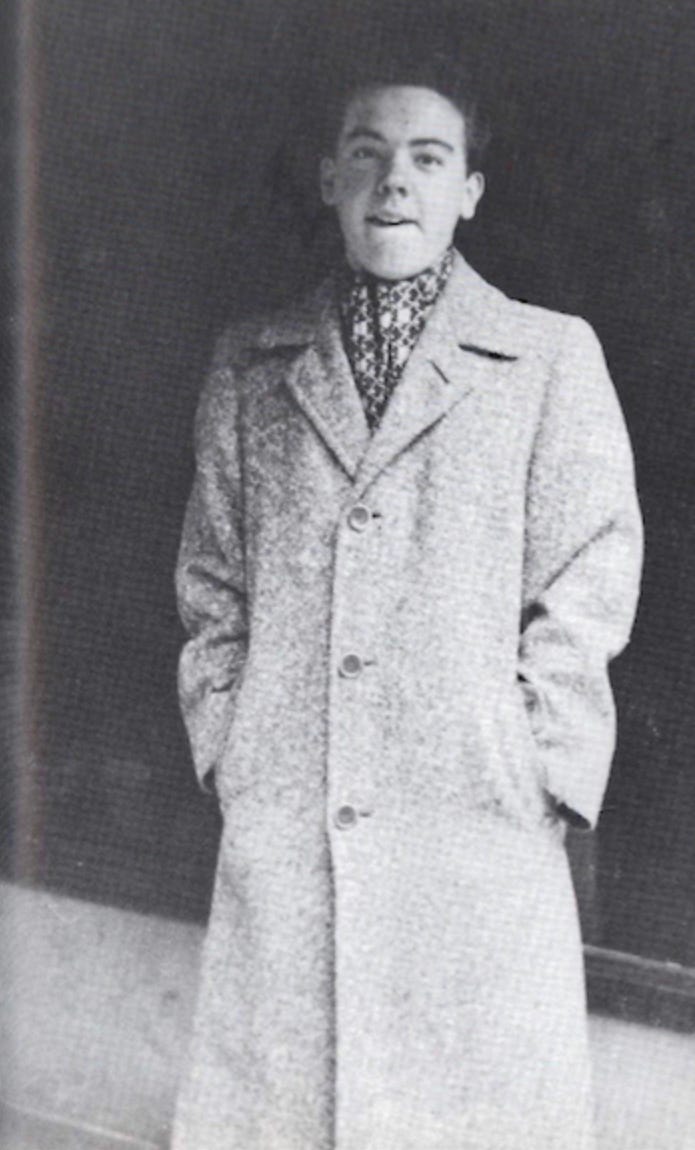

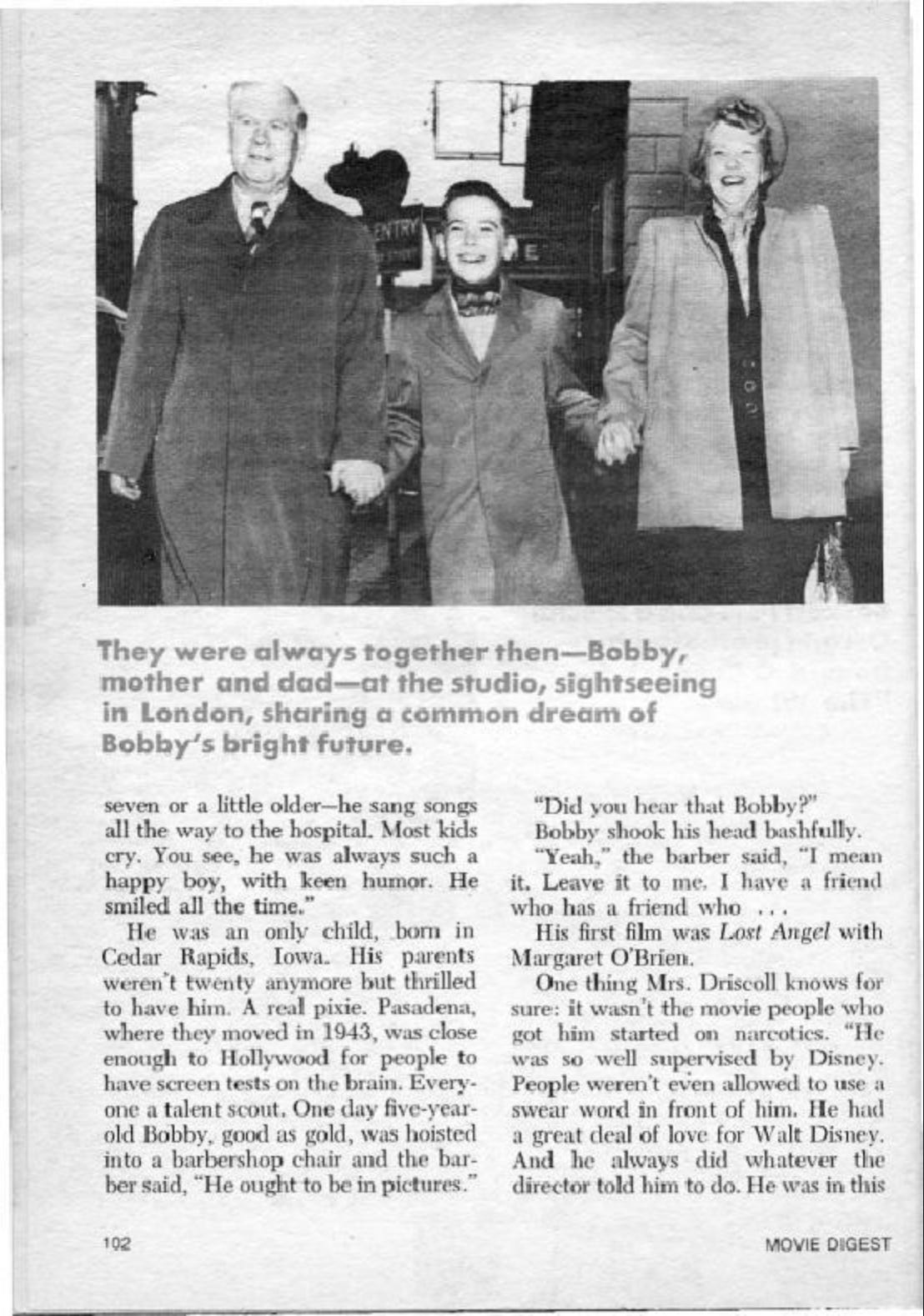

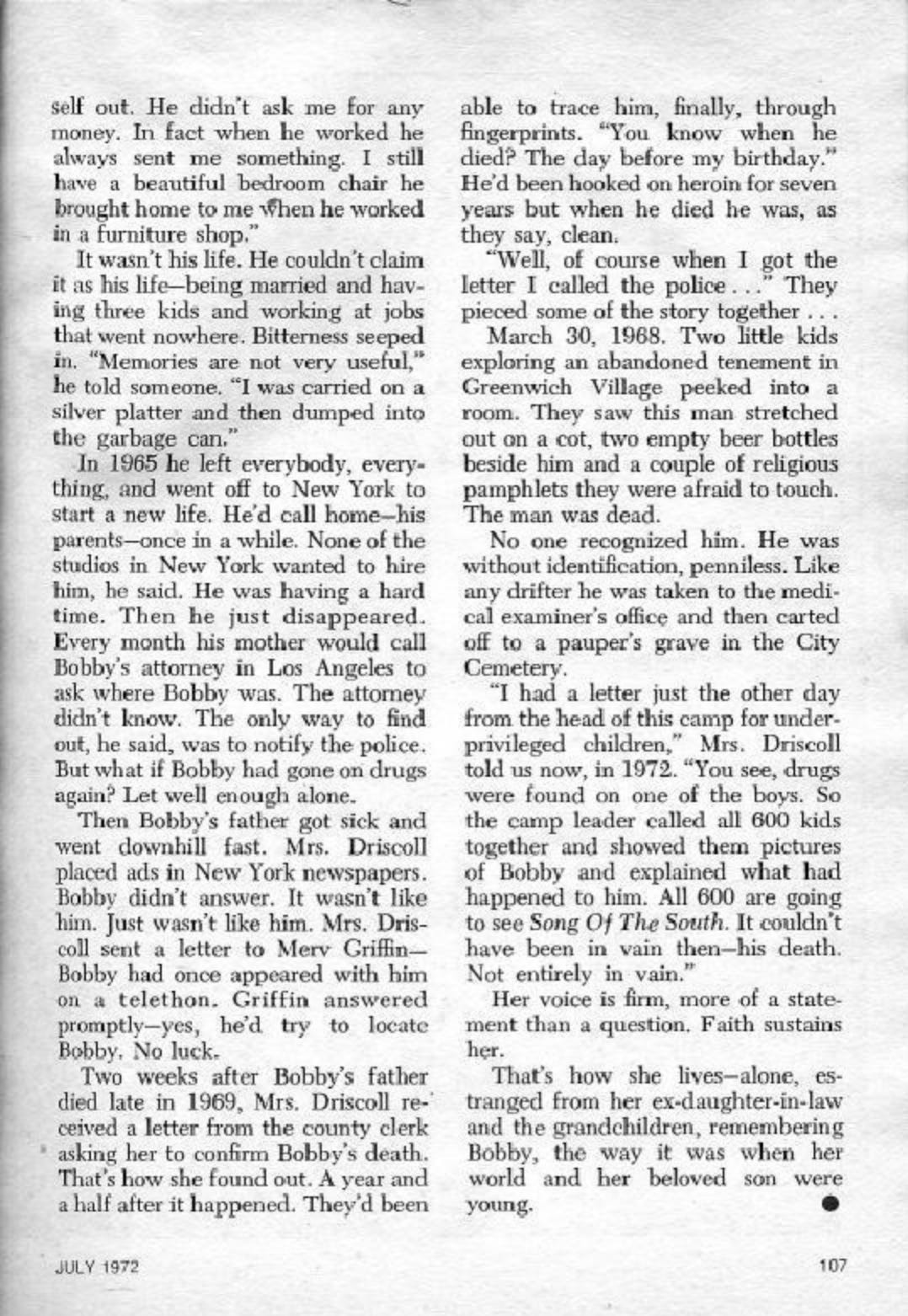

Bobby Driscoll was born in Cedar Rapids, Iowa on March 3, 1937 and spent his early years in Des Moines. His father, Cletus, was an insulation salesman who had grown ill from handling asbestos. On medical advisement, Cletus moved his family to Los Angeles in 1943. It took no time at all for 6 year old Bobby’s striking features and effervescent personality to land him roles in films for MGM, 20th Century Fox and Paramount. By nine, Bobby was already a seasoned professional on set, and agreeable to a fault.

Walt was unsubtle about the keen interest he’d taken in Bobby, and the amount of time and personal attention the preteen received from the studio mogul was impossible for staff to ignore. The success of Song of the South catapulted the 10 year old’s acting career into the A-list overnight. Walt, abundantly aware of the commercial value of his studio’s first live-action child star, began micromanaging Bobby’s career. Walt’s interest extended to private, one-on-one coaching sessions with the young actor as well as the occasional “work retreat.”

Disney Pictures, meanwhile, proceeded with a de facto merger with RKO through a distribution partnership which began in 1937. Bobby won Academy Awards for Best Juvenile Actor for his starring roles in the RKO-distributed So Dear to My Heart (1949) and The Window (1950). Walt personally coached Bobby most intensively for his role of Jim Dawkins in Disney Picture’s first live-action feature film, Treasure Island (1950). Filmed in the United Kingdom, Disney “brazenly flouted British law” by filming Bobby’s scenes without a Ministry of Labour permit and in violation of the minimum age requirement (Bobby was still 12 at the time.)

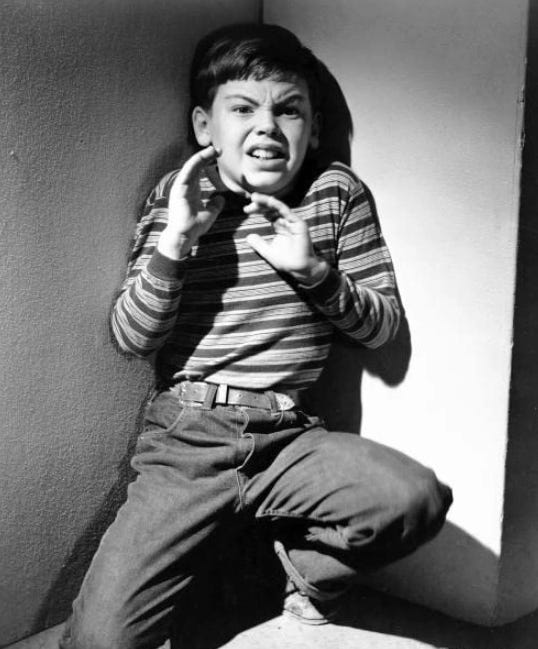

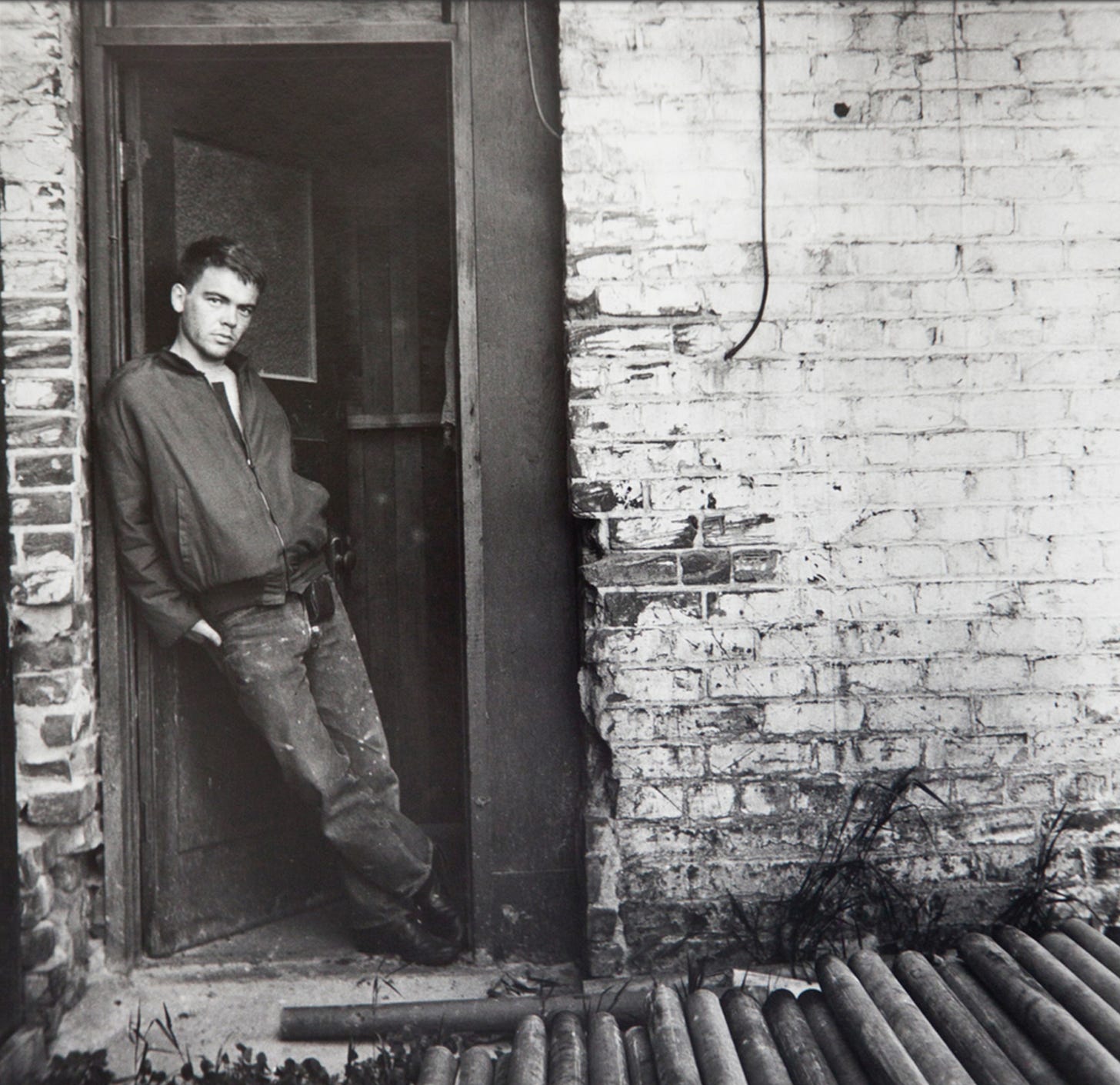

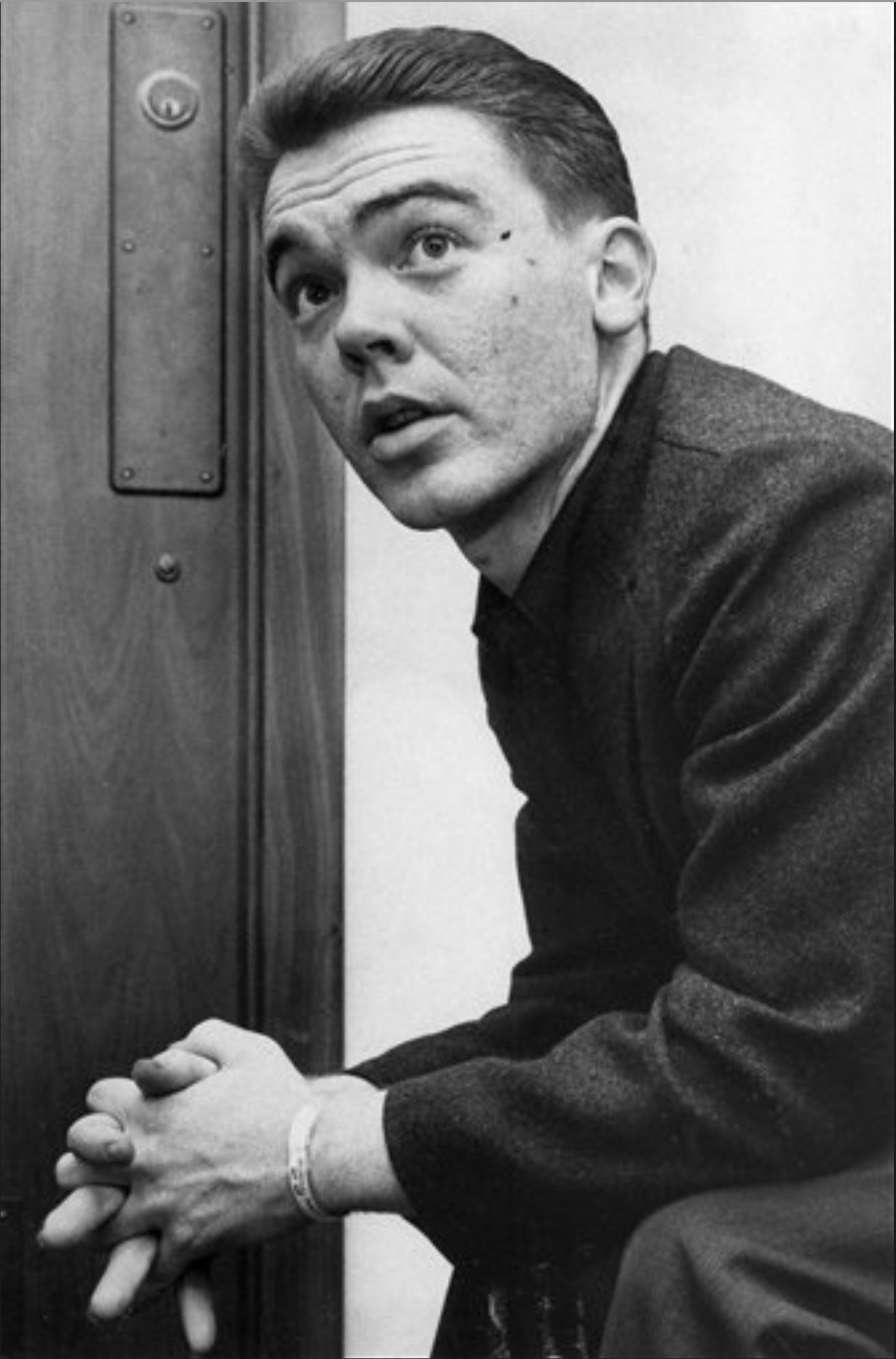

But something happened to Bobby Driscoll in between international child exploitation on set and Treasure Island’s premiere in the summer of 1950. Bobby Driscoll turned thirteen, and no Disney magic could fend off the all-too-familiar ravages of adolescence. The uneven growth spurts and acne most of us experience as we enter this phase of life are inherently problematic for someone who has, until this moment, established their brand on their youth. Unable to brace themselves for the cultural upheaval of the rock-and-roll era around the corner, Disney Pictures was already scrambling to mitigate the damage to their holdings wreaked by a typical onset of puberty.

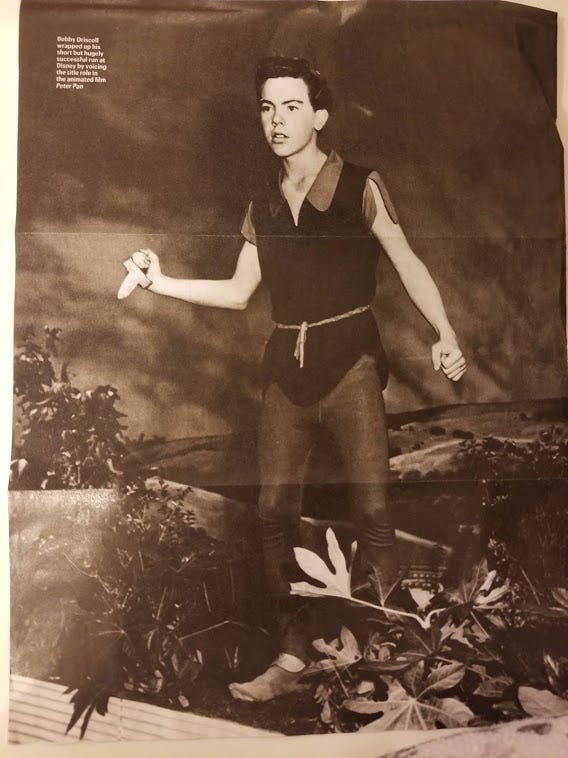

Walt for his part had turned his attention to the development of his theme park Disneyland and was unable to effectively advocate for his protege. Bobby provided voicework and rotoscoping for the lead role in Disney’s next animated feature Peter Pan (1953) but had minimal involvement in promotional efforts ahead of its February 5th release. Shortly after his 16th birthday, Bobby showed up for work at the Disney lot, only to be told at the gate, without explanation, he was no longer employed with the studio.

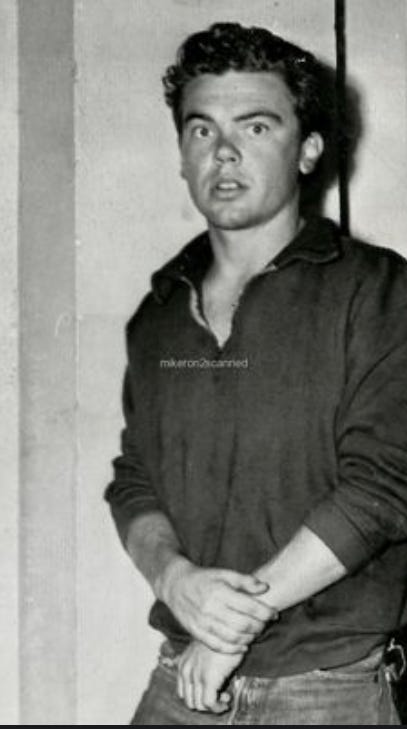

Bobby’s life as a Disney star had already been pulled out from beneath him, and his parents responded by pulling him out of Hollywood Professional School during his sophomore year. Thrust into public school at West LA’s University High, Bobby struggled to find acceptance anywhere among his peer group. His ostracism was compounded by his status as the first Disney has-been, and he was viciously taunted by his fellow students.

Seventeen year old Bobby soon found refuge in drugs. Still financially situated from his work with Disney, Bobby could comfortably afford a heroin habit for the moment. He was able to talk his parents into transferring him back to Hollywood Professional and graduated in May 1955. Acting work had grown harder to come by as Bobby struggled to transition to more mature roles. In July 1956, Bobby and a friend named Lester Ferguson were arrested for possession of marijuana. The charges were dropped, but not before Hollywood gossip queen Hedda Hopper wrote, “This could cost this fine lad and good actor his career.”

Bobby and Lester Ferguson were arrested again in Long Beach in August 1956 in the “Bean Shooter Incident,” the details of which remain hazy.

That December, Bobby, 19, eloped with Marilyn Jean Rush, 18, in Mexico against the wishes of both families. The two had their first son in August 1957, a daughter one year later and a second daughter March 1960.

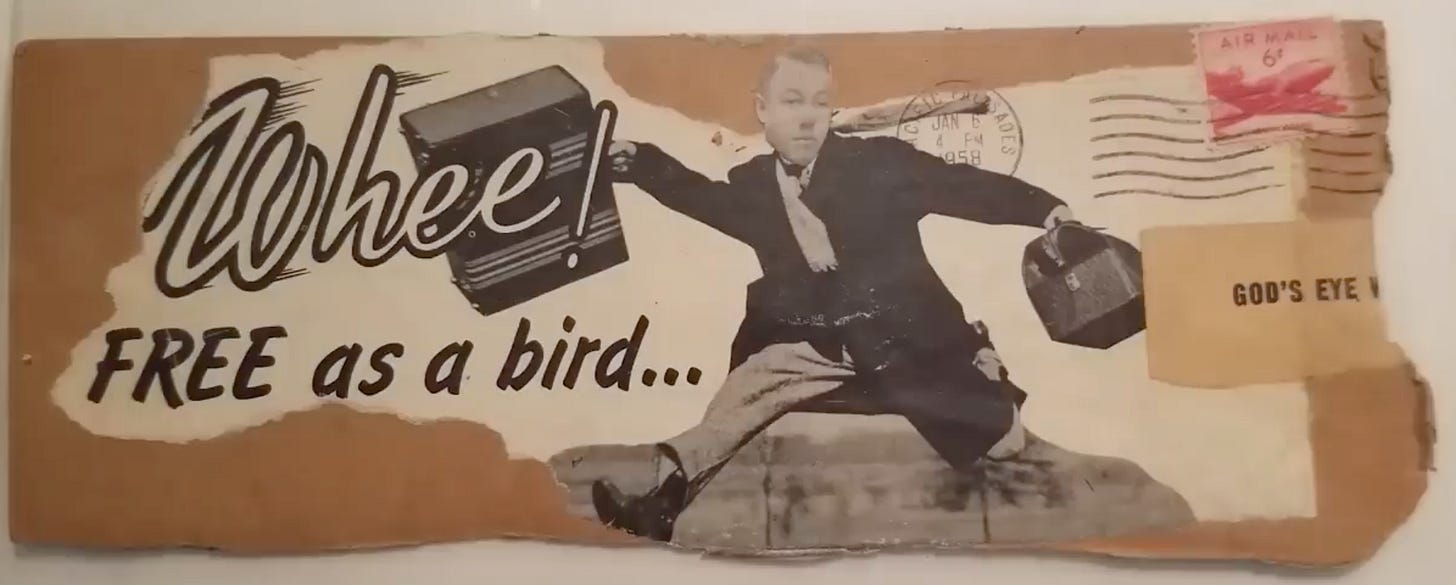

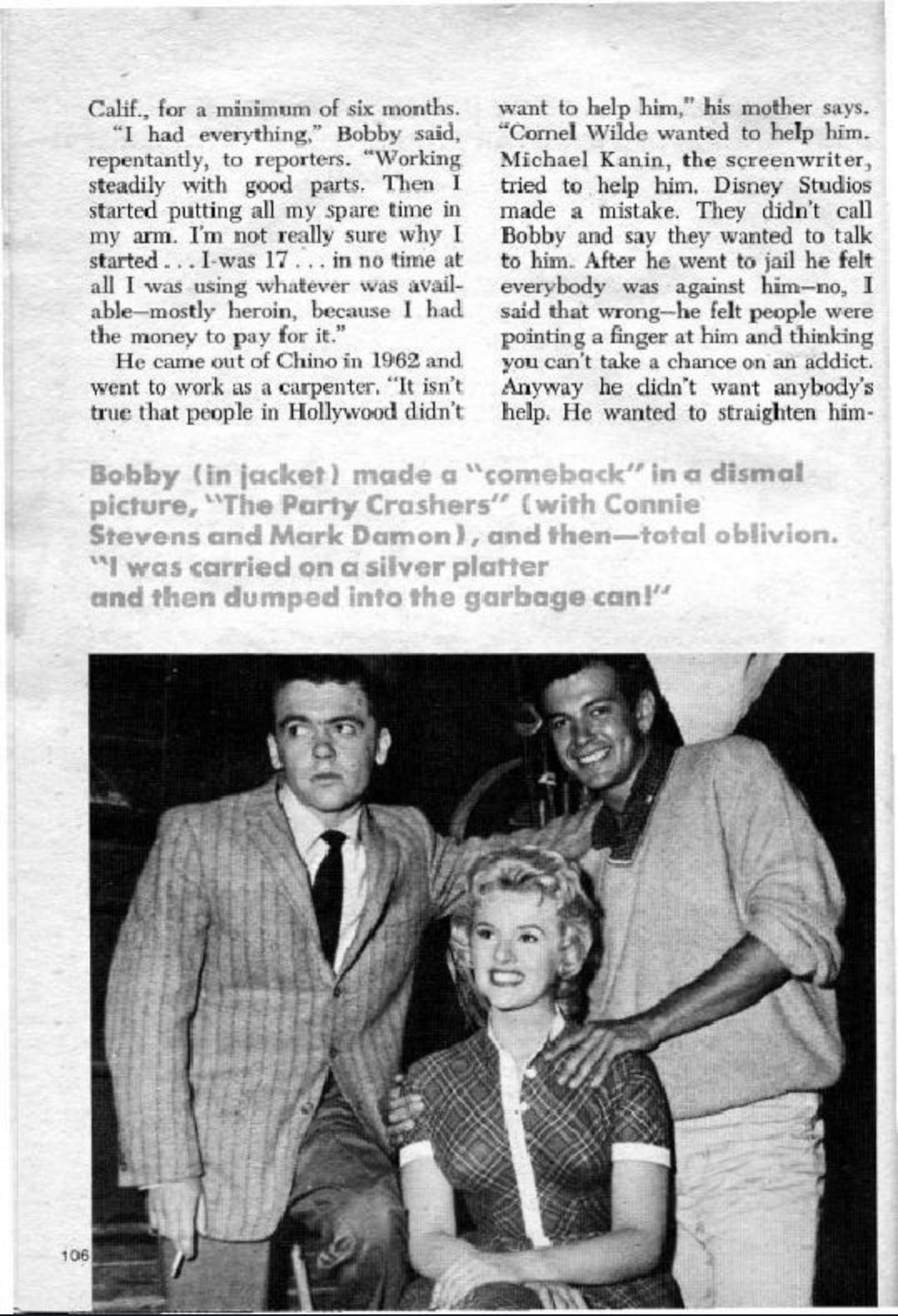

He made his final two feature film appearances in The Scarlet Coat and The Party Crashers, both in 1958. By then, alongside substance use had come a growing interest in the arts. Jack Kerouac had used the term “beat” to refer to the addicts, prostitutes, thieves, sexual predators and con artists he gravitated towards, who he saw as “beat-down” and discarded by society.

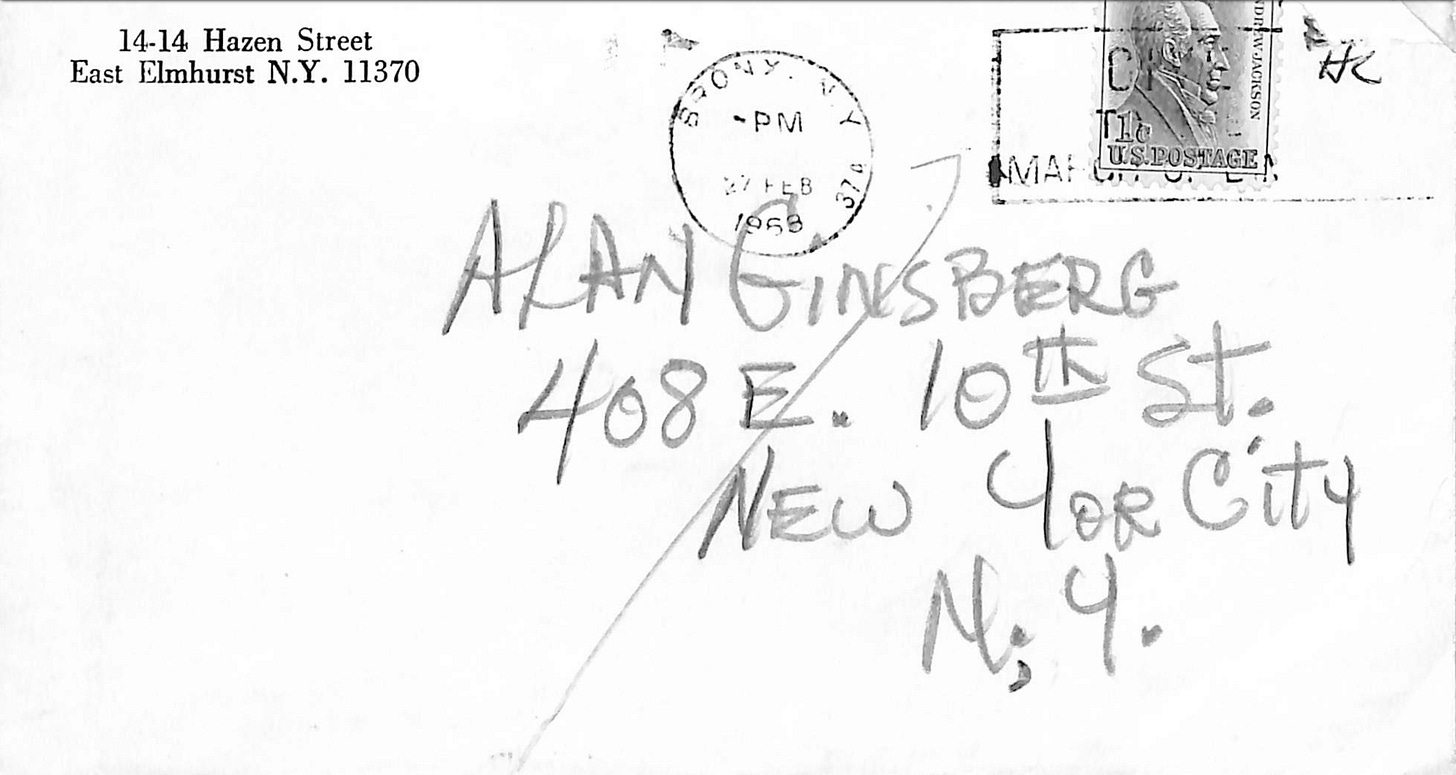

One “beat” artist Bobby admired in particular was poet Allan Ginsberg. Ginsberg’s writings were frequently informed by his penchant for sexual relations with prepubescent boys.

Bobby also pursued a passion for visual arts, with his preferred medium being collage.

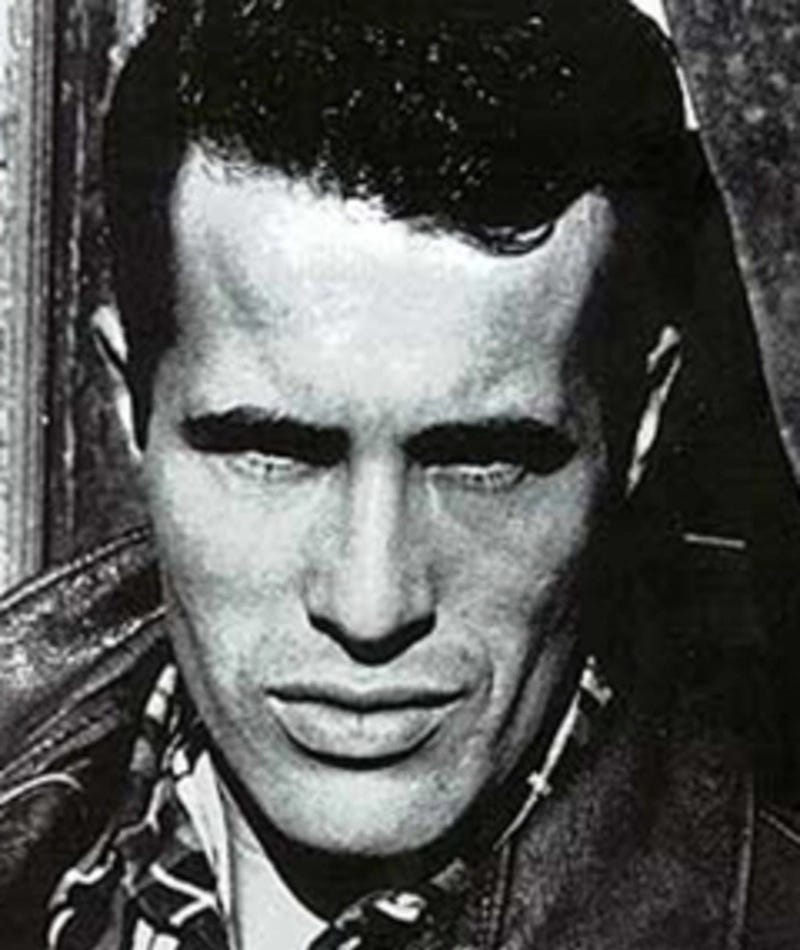

On October 11, 1959, Bobby was arrested on narcotics charges along with two other men in New York City. He was acquitted at trial. Bobby was arrested on June 19, 1960 for assault with a deadly weapon after pulling a gun on two hecklers in Pacific Palisades.

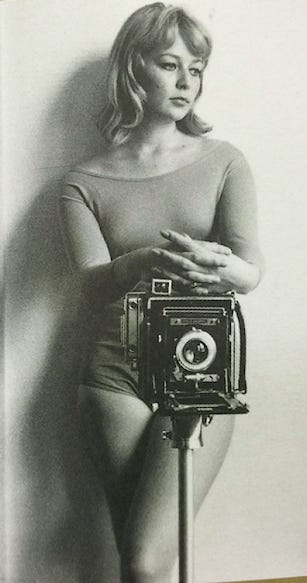

By this time he and Marilyn had divorced, and Bobby began dating Suzanne Stansbury. The two were arrested April 4, 1961 after robbing $450 in cash and narcotics from a veterinary clinic. The charges were dropped for lack of evidence on April 21.

On May 1, 1961, Bobby was arrested for passing $45 in bad checks. The next day, he was arrested again on narcotics charges.

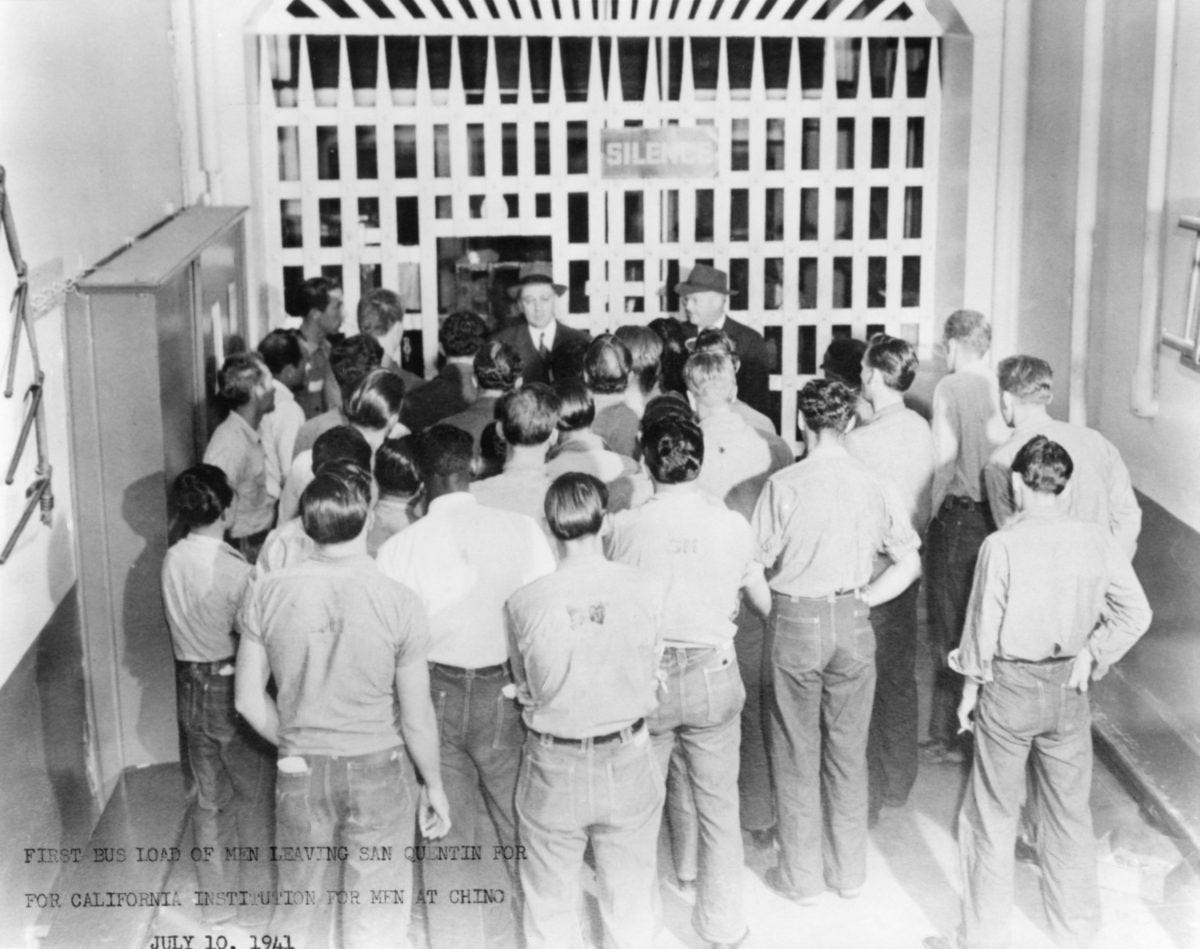

This time, the judge sentenced him to six months at the Narcotics Rehabilitation Center at Chino - Men’s Institute at Tehachapi. The case was presented as a progressive victory in the criminal justice system; the first Disney star was now the first addict to be treated as a patient with an illness instead of a criminal.

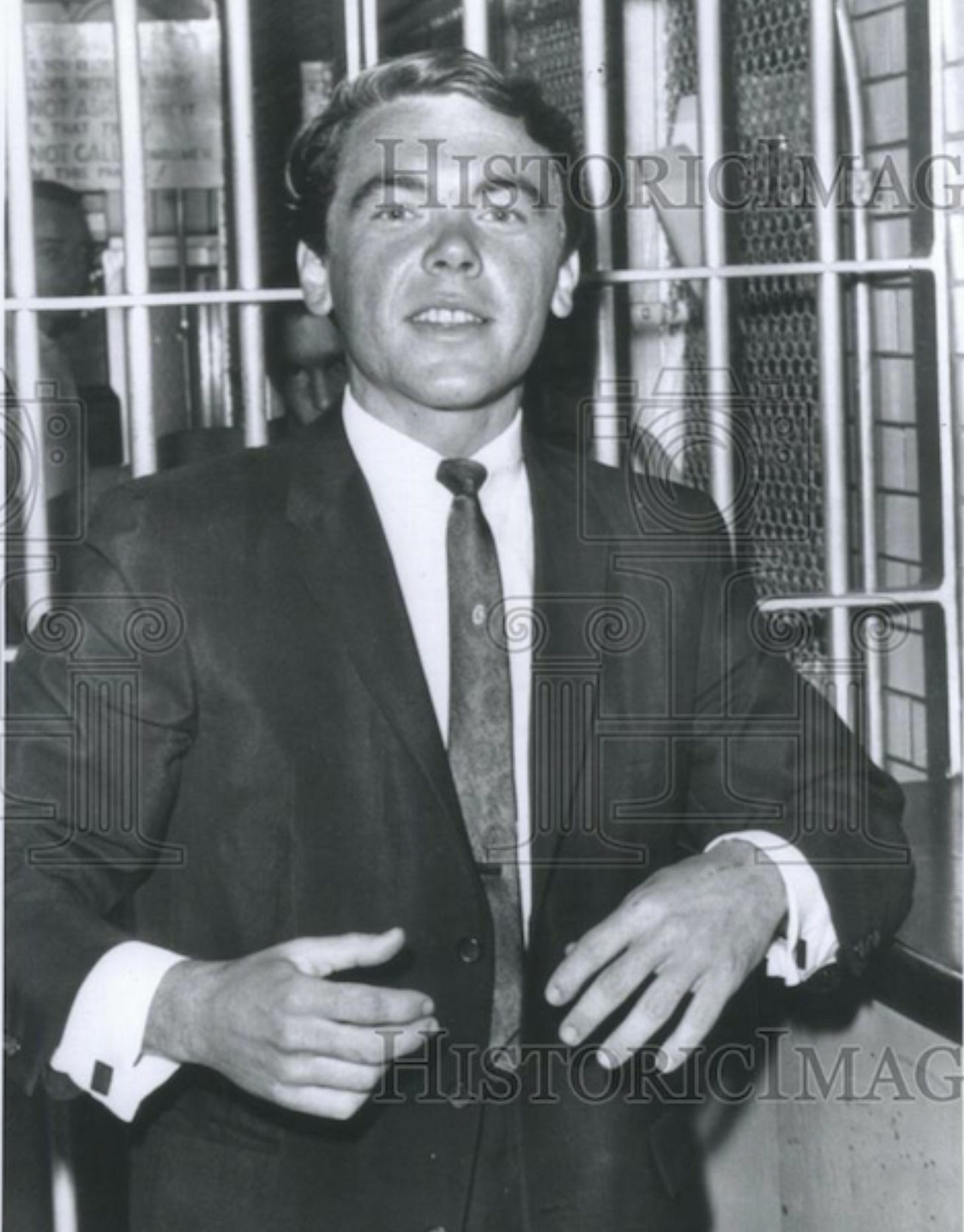

At his sentencing hearing, Bobby remarked: “I had everything…was earning more than $50,000 a year, working steadily with good parts. Then I started putting all my spare time in my arm. I was seventeen when I first experimented with the stuff…mostly heroin because I had the money to pay for it. Now, no one will hire me because of my arrests. I’m looking forward to the coming months in Chino.”

After his release in 1962, Bobby said of his experience in rehab: “there weren’t any nurses there, that’s for sure.”

At 26, Bobby was wholly unemployable as an actor in Hollywood. He married his second wife, Sharon “Didi” Morrill in 1963.

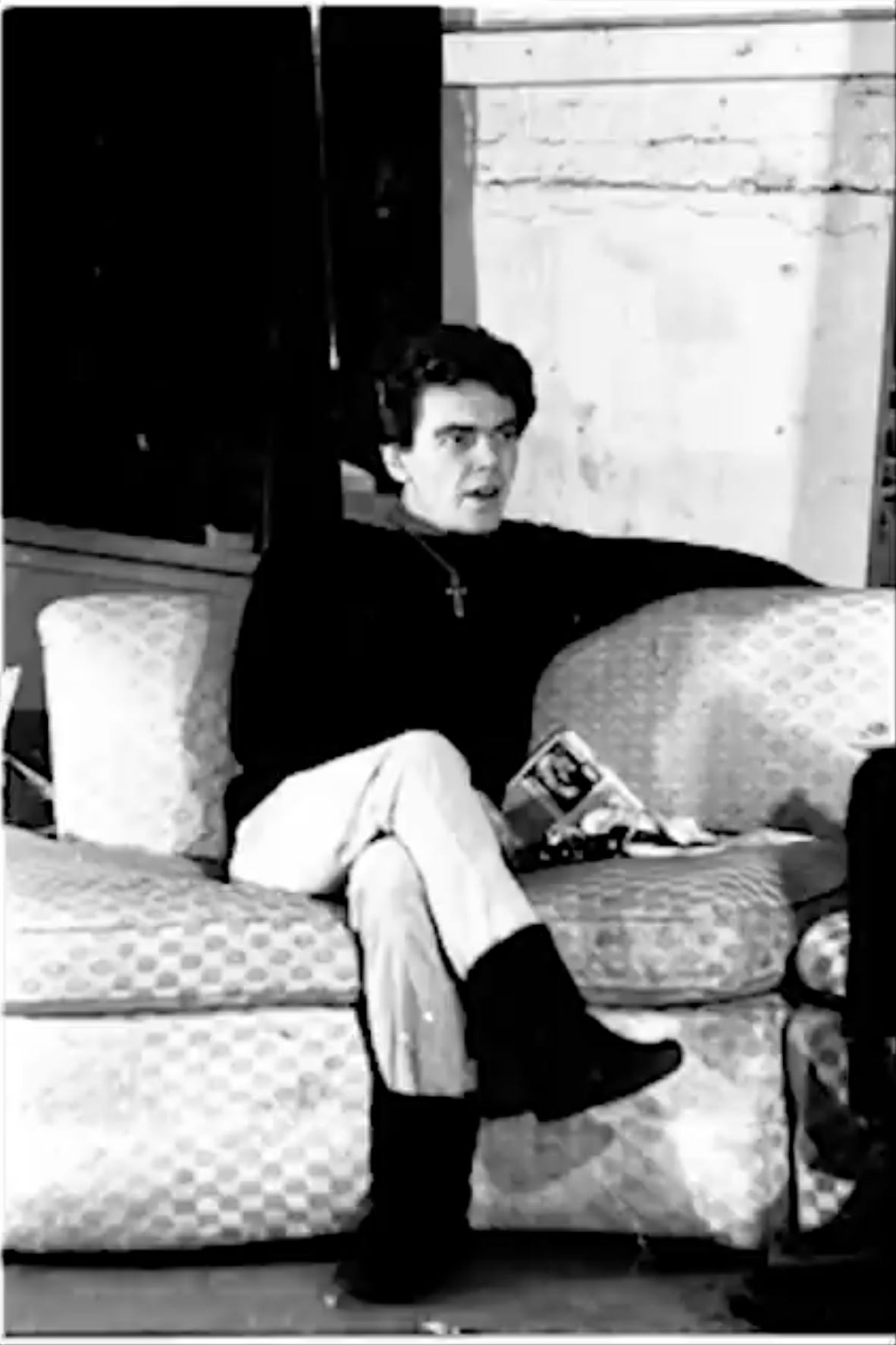

When his parole expired the following year, the two moved to New York City. Didi in particular hoped to revive her husband’s career on the Broadway stage, but this would not come to be. Bobby was able to ingratiate himself into the Greenwich Village art scene through his force of personality and what celebrity cache he had left. He became a fixture of Andy Warhol’s art collective The Factory, which lead to his final screen credit. In Piero Heliczer’s plotless silent short film Dirt, “Robert Driscoll” briefly appears dressed in a nun’s habit, flanking a sailor on leave who serves as a more central figure throughout the one-reeler.

Bobby’s inability to find a second life as an artist was offset by near-unlimited access to heroin and methamphetamine, the en vogue substances at the Factory in the mid 1960s. His life reduced to a perpetual cycle of rounding up funds though begging, conniving and trading on his name to feed his habits, or, more aptly, to fend off the inevitability of withdrawal.

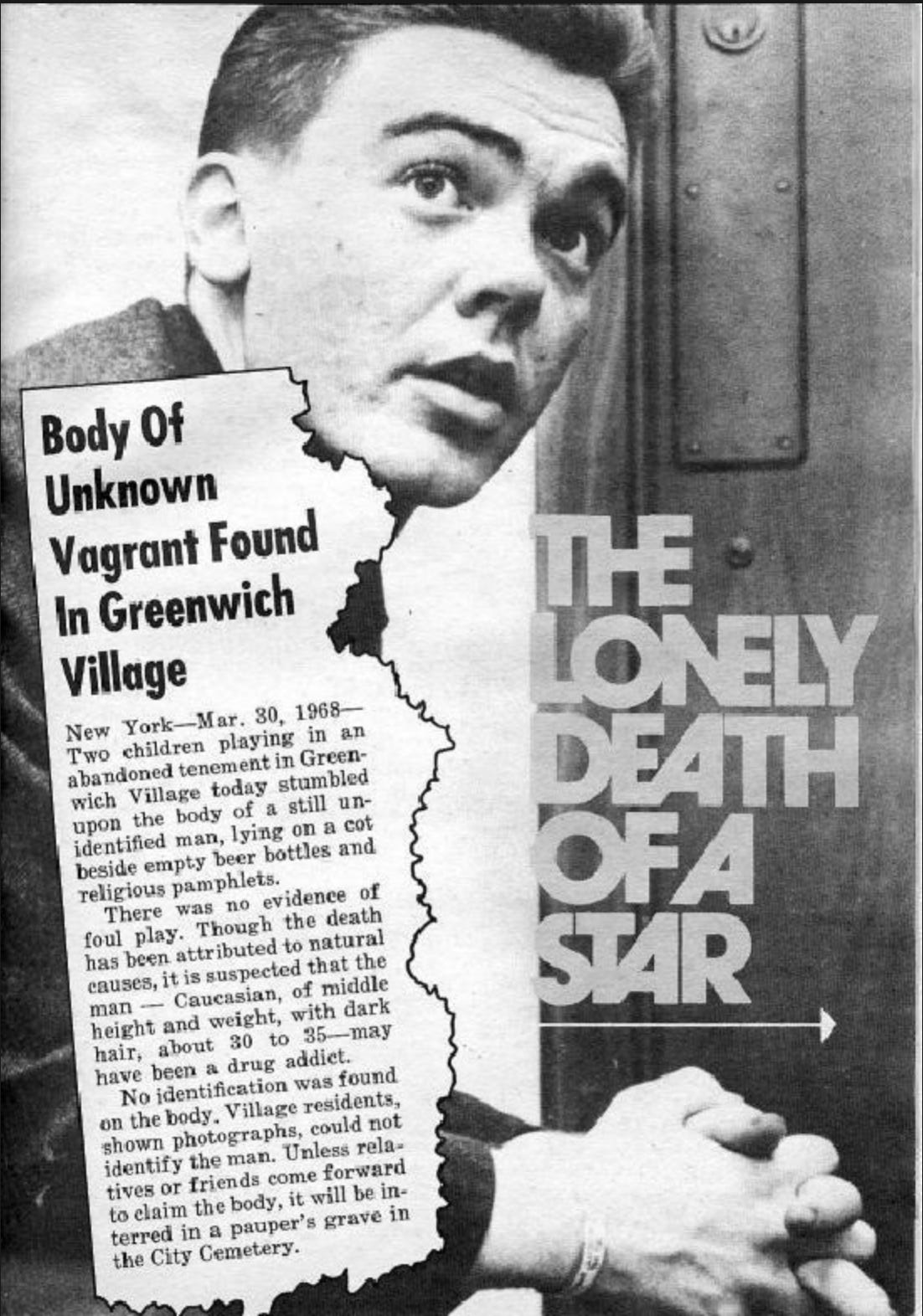

On March 30, 1968, two boys were playing in an abandoned East Village tenement at 371 East 10th Street. They came across a recently deceased male in a cot. Lying next to him were two beer bottles and a handful of religious pamphlets.The coroners determined the cause of death to be advanced atherosclerosis due to heavy substance abuse. A toxicology report was positive for methamphetamine. With no identification, the body was buried in a pauper’s grave at Hart Island.

Cletus Driscoll died the following year, and in the process of settling his estate, Disney executives tracked down Bobby’s remains and notified the family. In 1971, Disney re-released Song of the South in theaters to wide acclaim. For a moment, Bobby Driscoll was celebrated once again as a star.